At Drive Change, we lobby to exclude medicinal cannabis users from the draconian drug driving detection laws. There are numerous reasons these laws are just plain wrong. But, one of the arguments we keep coming up against is road safety. Opponents of law change are adamant that these laws are designed to improve road safety.

The fact is – our current drug driving laws do not improve road safety.

This blog analyses the current drug driving laws and road safety and provides evidence for why these laws must change.

Correlation and Causation: The Basics

It is stating the bleeding obvious that there is a distinction between correlation and causation.

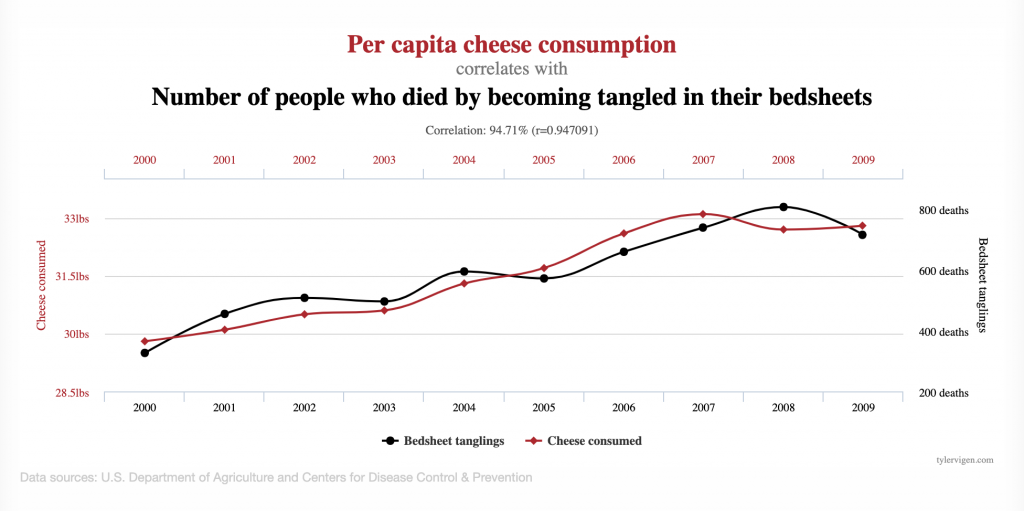

Just because two things occur does not mean that one causes the other. There are some marvellous websites that exemplify the difference between causation and correlation. My favourite one contrasts the purchase of cheese per capita and the number of people who die from becoming tangled in their bedsheets.

Stunningly, this correlation can be mapped by double lined graphs for decades. These results certainly do not prove that eating cheese causes death in this manner or that death in this manner leads to eating more cheese by the bereaved. It is possible, of course, that these two arguments are true – but it is more likely that there are other factors at play. In that case, the old demon of coincidence.

Yet this classic and basic error is repeatedly made in drug detection driving and road trauma.

Just because individuals who died in car accidents had a drug in their system does not mean the drug was the main cause of the accident, particularly relating to cannabis medicine.

Examples of Over-Egging the Pudding

Every time someone mentions law reform, someone else will trot out the tired old argument that the presence of illicit drugs in your system leads to more deaths and injury on the road.

For example, in opposing drug driving law reform in NSW in 2020, Scott Farlow MLC stated in parliament:

“NSW crash data indicates that since 2014 there has been a 7% increase in the number of fatalities and serious crashes directly attributed to the presence of an illicit drug.”

The media, even responsible mastheads, often do not help. For example, there is this headline from the Sydney Morning Herald, also in 2020:

“On Ice or Doped Out – Drug driving deaths rise across Australia.”

This article boldly declares that drugs contribute to one in five deaths in New South Wales and cites research by Dr Mathew Baldock (more on this shortly).

“Driving with drugs in your system is not only illegal, it’s extremely dangerous and puts your life and the lives of all other road users at risk.”

Unfounded statement by the Director of Road Safety in NSW

And all this “research” leads to fiction-based declarations like this by police, politicians and, in this case, the Director of Road Safety in NSW.

Research Findings: No Causation

In NSW, the research shows that in the nine years from 2010 to 2018, 21 per cent (384) of the 1818 drivers or riders who died on NSW roads had an illicit drug in their system. In Baldock’s study, it was over 15%, with around 9% amphetamines and 6% THC. There are other similar studies with results in that range.

However, nowhere in the actual published research is there anything like proof of causation.

In other words, there is nothing to suggest that even just one of those deaths was caused by the presence of drugs, a classic example of confusing correlation with causation.

A careful analysis of Baldock

In South Australia, as in other states, those killed in road accidents are subject to mandatory blood tests. The cut-off level for THC is two nanograms. In the Baldock study, they tabulated the results of this and found that around 6% of those who died had a detectable level of cannabis in their system.

And from this, the authors and others have claimed a causative connection – THC presence leads to deaths. To those blessed with the knowledge of correlation/causation errors, the problems with this argument become immediately apparent.

To show causation, one would need first to prove that at this level, drivers were adversely affected by the THC in their system. Given that cannabis can be detected for up to six days in the blood, that would be impossible.

Second, there would need to be evidence that the driver was at fault. There is no analysis of this in the research, and many of those may have been the innocent driver. We’ll never know.

Third, there would need to be research showing that 6% with THC presence is higher than the norm amongst the population profile of those who died. Research shows that around 30% of those aged 18 to 24 have recently used an illicit drug, with cannabis use by far the most common.

It is entirely possible that the 6% figure is an underrepresentation. Of course, that does not mean that cannabis consumption makes drivers safer either – that would be confusing cheese and bed strangulation as well.

Fourth, to rely on this research to make the causation argument, one would hope to find a single statement linking the presence and the deaths within the published study itself. There is none. And that is because the authors would not want to be the laughing stock of their peers for making a research 101 error.

Fifth, there is not one iota of evidence that a single driver was driving while taking medication under a prescription. The demographic profile of those with prescriptions for cannabis containing THC is markedly different from those who are most commonly involved in fatal motor vehicle incidents.

According to TGA, the average patient is about 50 years old, female and has access to private funds for expensive medicines. Further, they are actively seeking to minimise the psychoactive effects – they are not using a bong at a party, getting in a car and having a collision on the way home.

Finally, there is no evidence that these laws have reduced the road toll at all in any jurisdiction in Australia. When random breath testing for alcohol, seatbelts, speed limits and airbags were introduced, there was a marked decline in the road toll.

Although there are over 500,000 drug driving detection tests per year, there’s still no evidence the roads are safer due to random roadside testing.

Conclusion

There is no correlation between the presence of THC in saliva and impairment. More importantly, there is no evidence that driving with a detectable level of THC increases the risk of road trauma.

Efforts to link the two exemplify a classic case of confusing correlation with causation. This mischief is not just inaccuracy; it serves to provide a significant hurdle to reforming laws that unjustly and unjustifiably discriminate against medicinal cannabis users.